Antwerp in Aphra Behn’s time

Antwerp’s history goes back at least two thousand years – there was a Roman settlement, which in turn was taken over by Germanic tribes – like all ancient cities, it has mythical stories about its foundation, in this case featuring a vicious giant named Antigoon who extorted tolls from boatmen on the River Scheldt and cutting off the hands of any who refused. The city developed beside the river’s estuary, and a thriving port grew up – in the present day still one of the twenty biggest in the world.

The Antwerp where Aphra Behn settled her party into a middling priced inn was past its glory days of the previous century. But it was still a bustling, prosperous international city. Visitors mentioned a skyline with churches, windmills and towers. Its so called golden age was behind it – the sixteenth century had brought great prosperity, status and the start of trade with the New World. The city featured the first custom built commodity exchange, and was a centre for international finance of all kinds – it was from Antwerp that Henry VIII had borrowed money when he had run through the sources of revenue available at home, and his was not the only government to prop up their liquidity from the Antwerp Bourse. The city also became home to new trades, notably in diamond cutting and sugar refining. The sixteenth century was not, however, quiet politically as it featured uprisings and a fair share of the blood baths that accompanied the Reformation over most of Europe – most notably its sacking by Spanish troops in 1576, when as many as 7,000 citizens died.

Alongside the economic prosperity, Antwerp was a cultural hub. The artists Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony Van Dyck were born here; Pieter Bruegel settled and spent most of his life in the city. It was the home of many of the most innovative of early printers, and was the place where esoteric and even dangerous books were printed. Antwerp was home not only to creators but collectors; during the seventeenth century it became the fashion among wealthy art lovers to commission pictures of their personal art galleries, sometimes with the owners included in the picture. This was a way of demonstrating their wealth, taste and status – in Britain it was more often the patrons’ country estate that featured in the picture. This was a city with a population of perhaps 100,000 – the more prosperous streets were lined with tall houses, many with elaborate stonework; there were large, impressive public buildings including livery halls, and an expansive early sixteenth century cathedral. The River Scheldt had long been closed to shipping for political reasons, but this was still very much a meeting place for all nations.

The early seventeenth century had seen some lean years for Antwerp. But by the 1660s the city had regained some equilibrium. This was a city, ruled relatively peaceably by a merchant elite, where people of many nationalities lived and visited. It was a place where British exiles of all stripes had taken refuge in the years after the Civil Wars when not only the children of the executed Charles I and his widowed Queen, Henrietta Maria, but some of the hundreds of their adherents who had followed them into exile, had joined the community that spent the years between 1649 and 1660 following them round Europe and waiting for the day when they could return home. The tall, saturnine young gentleman who to some was King Charles II and to others “the man Charles Stuart” rarely spent more than a few months in one place as he and his entourage of increasingly needy followers moved between European capitals, by all accounts changing locations as their hosts found them a financial liability or because the Republican regime in London became restive. The Earl of Newcastle, one of the most loyal of Royalist adherents, became resident in Antwerp, and hosted a grand event for the young king, honouring him and his court with the grandest of entertainments.

When the English regime changed so abruptly in 1660, many exiles returned home. But not everyone was delighted by the prospect of the restoration of monarchy. The official undertaking by the new Royalist regime was that a Treaty of Indemnity and Oblivion, passed in 1660, promised to forgive most of what had taken place over the past twenty years. With the exceptions of “piracy, buggery and rape”, and specified people who had promoted the killing of Charles I. The spin was that the newly returned king wanted nothing better than to settle back down in peace and harmony, with the minimum of recriminations.

Inevitably the reality was a little more complicated. And certainly a good many of those who had been closely associated with those who had been in power in the previous twenty years now in turn left the country. Many made their peace with the king – as he wryly remarked, as everyone he met was so happy to see him, it must have been his own fault that he had stayed away so long – but some were too suspect to be safe. And some had become convinced republicans and were unhappy to live in a country with a king at its head. Some of the unhappiest, for example Algernon Sidney, stayed in England to argue their case. But others, for example William Scot, who was the person Aphra Behn was tasked with persuading back to England, decided that life on the Continent was safer. Some parts of the Continent were safer than others – the Low Countries, a few miles north of Antwerp, were safest of all; Antwerp, not reliably Protestant and with Spanish connections, was less comfortable.

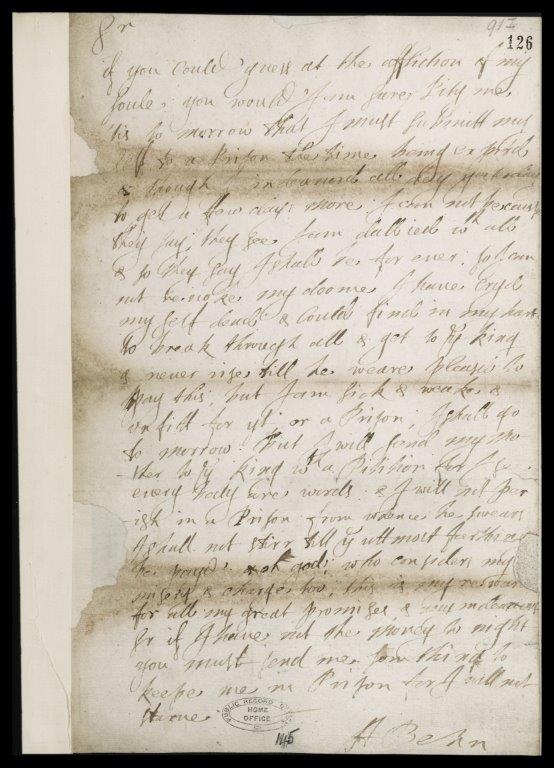

Aphra Behn’s visit to Antwerp was clearly not a happy one. She had been set up to fail in terms of her spying mission, because of her own inexperience, because she was poorly briefed and because William Scot was both too wary and too sophisticated to make any undertakings to her. He was reluctant to spend any time in Antwerp, which he regarded as less safe than the Low Countries a few miles away. And Behn’s most immediate problem was lack of money. She had been given a £50 advance (the equivalent of something in the low thousands today), but was travelling with her mother, brother and servants, and this was an expensive city. Behn’s letters home became increasingly less concerned with any progress she might have made with regard to Scot, and more concerned with asking the spy masters for more money. It may be a sign of her inexperience that she had not obtained any kind of agreement in advance about how much money she could spend and arrangements as to how it would be paid. As it was, the landlords of the Rosa Noble Inn in Katalynevest became suspicious about Behn’s ability to pay their bill. Despite an interim payment from London, which covered only a proportion of what she owed, Aphra Behn finally borrowed money from a friend of a friend so she could pay her bills and return home. It is unlikely that she ever visited again.

Clio’s Company (registered charity no. 1101853) is grateful for generous financial support for this project from The Portal Trust