London Theatre

Famously, London theatres were among the first casualties of the civil wars; Parliament, in control of the capital, closed them down in 1642, citing the “times of humiliation” as the reason. Through the following years, first of war and then of commonwealth, performances in public remained illegal. There were, however, concerts in private houses. Sometimes these seem to have included theatre and dance, and it seems that a full scale opera was staged in the 1650s.

Most actors had left London, mostly to fight for the king. Among these was Sir William Davenant, who ended up back in 1650s Aldersgate Street by way of Henrietta Maria’s court in exile, a stint in the navy and imprisonment in the Tower of London on a charge of treason; his life is said to have been saved by the intervention of John Milton. Davenant and his wife held musical entertainments in their home in the 1650s, and were ready and waiting for the Restoration when it came.

Charles II lost no time in reopening the theatres on his return in 1660. In August of that year Sir William Davenant and Thomas Killigrew had received licenses to open, respectively, the Duke’s and the King’s Companies. Some things, including the need for theatre companies to be officially employed by the great and the good to stop them counting as “rogues and vagabonds”, had not changed. But much had: the old theatres, including the Globe, had been destroyed; and the king brought new tastes and fashions with him. Most notably, women were now to play the parts of women, leaving behind a past which had decreed only men and boys were to appear on the professional stage.

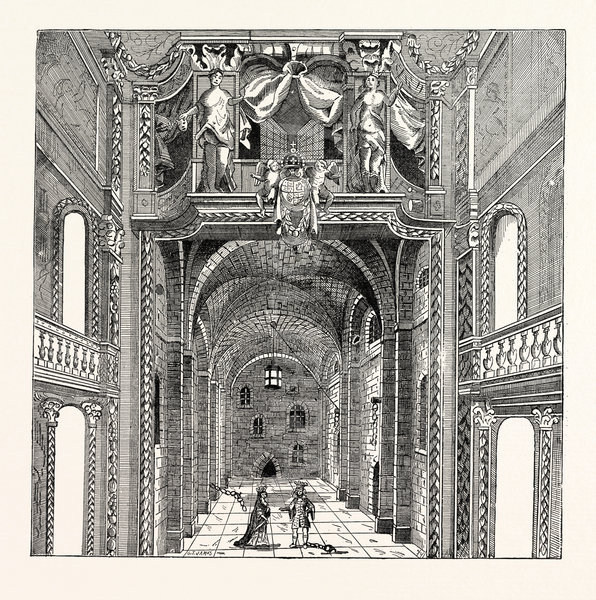

By the late 1660s, when Aphra Behn was in London seeking her break as a playwright, the two theatre companies were successfully established. In the early days both companies played in adapted tennis courts; both then moved to custom-designed theatres in the new style, King’s to what would become the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Duke’s to Lincoln’s Inn Fields and then Dorset Gardens. The new theatres, which appear to have had an audience capacity of perhaps 700, had proscenium arch stages and were designed with space back stage to allow stage machinery, making multiple special effects possible, and the capacity to accommodate multiple changes of scene. Lighting was provided by central chandeliers, by rows of candles at the front of the stage and by candles with reflectors at the sides of the stage. All this added up to a horrendous fire hazard: and indeed many theatres of the time were destroyed by fire. So the auditorium remained lit throughout the performance – and there appears to have been little expectation that the audience would necessarily be quiet to allow the cast to make themselves heard.

Londoners of all classes went to the theatre, often attending several times a week. The King and the court attended regularly, but so too did tradespeople and servants. Ticket prices were kept affordable, with the cheapest seats no longer in a pit at the front of the stage but high up in the gallery. So the two theatre companies had a constant need for new plays to stage. Each of them had the rights to some of the “old canon” – pre civil wars plays, the works of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson and Webster were still popular. But these were not enough. The companies reckoned that a run of more than three months was a successful one. So the system was a repertory one – the actors were expected to attend rehearsals for the next show in the mornings and perform the current one in the afternoons. And audiences expected several hours’ entertainment for their money. Plays routinely included songs, instrumental music, dancing and spectacular scenes. There would often also be incidental music and dance in the intervals that were necessary to change scenes.

By the time Aphra Behn became a professional writer the two theatre companies included a number of highly regarded actresses, as famous as their male counterparts, but paid very much less. Even the best regarded actresses were paid perhaps £3 per week, while some of the men were on £5. The company members all counted as Royal servants, and the women were given fabric to make livery cloaks. They were, however, expected to tolerate visits to their shared dressing room by members of the court, who regarded actresses as fair game. The theatre managements were aware of what was going on but the trouble makers were of such high status that they could not be challenged. And the king, although he was more courteous in his behaviour, had set a precedent of a kind by taking an actress, Nell Gwynn, as a lover.

In these years Sir William and Lady Davenant continued with their private studio theatre at their home, Rutland House in Aldersgate Street, and it seems to have been here that the first drama school, The Nursery, had its headquarters. And here, almost certainly, Aphra Behn was offered her first work in theatre, writing and directing her own first plays for the drama students to cut their teeth on. We know that “the young people” were allowed to appear on the main house stage in quiet times and in the summer holidays. It is also likely that Aphra Behn wrote some early plays, now lost, that were staged, or at least tried out, in the studio theatre at Rutland House. Thomas Killigrew ran his two careers as spy master and theatrical impresario in tandem, and appears to have provided her with introductions and support.

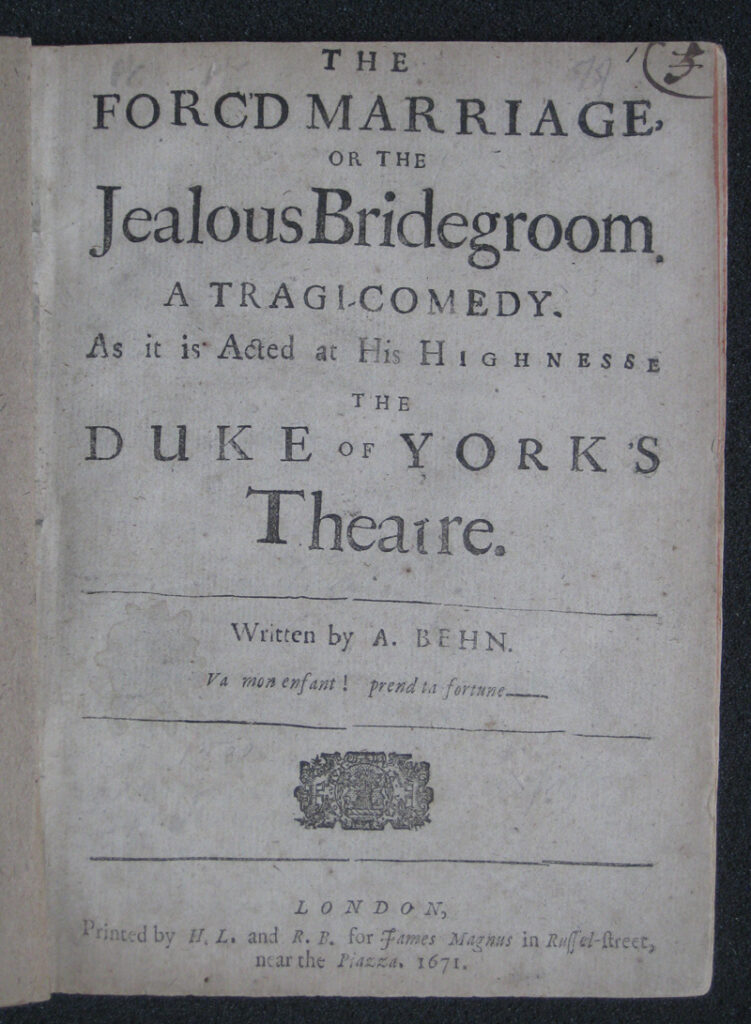

But it was to be the Duke’s Company that provided Aphra Behn’s main house debut. Sir William Davenant had died in 1668, since when his widow Mary had run the company even though her young son, and Thomas Betterton were nominally in charge. And on 20th September 1670 “The Forc’d Marriage” opened. A tragicomedy featuring kings, generals. Two intertwined love stories, and themes including the proper use of royal authority, It was a modest success, running for six performances, meaning the author received the profits for the third and possibly the sixth show. The prologue made full use of Behn’s sex and past as a spy, included such lines as “the poetess, they say, has spies abroad….”

Even after all the expenses Aphra Behn would certainly have had to pay to get her play staged, it is likely she made about £20 from “The Forc’d Marriage” – enough to enable her to continue to write, although she was always to add to her theatre income by accepting whatever writing commissions she could get. She also had each of her plays published – another source of income, although allowing her name to appear in print was one of the reasons censorious people disapproved of her: it was acceptable for a woman to circulate her work in manuscript among her friends, but not to have it printed and sold to all comers.

Other playwrights – all of them men – were various in how welcoming they were to a female rival. Some were to publish accusations that, as no woman could possibly write a play unaided, Behn must have a lover in the background who had done the creative work. But it was the audience numbers that ultimately counted, and for the next twenty years these were good enough to allow Aphra Behn’s work to be staged on equal terms alongside the new works of Etherege, Shadwell and Dryden and revivals of the old favourites of the years before the Civil Wars.

Clio’s Company (registered charity no. 1101853) is grateful for generous financial support for this project from The Portal Trust