Food and cooking in Aphra Behn’s London

There is little mention of food and eating in Aphra Behn’s work – the occasional reference to a “great dinner”, to a bowl of the milk punch she liked or to brandy in a pub. And the occasional feast, but certainly nothing so domestic as shopping or cooking. And it may well be that Aphra Behn was careful not to show any interest in a subject that might have earmarked her as being only fit to do the catering.

There is a wealth of information about what and how the rich ate at this time. Food and drink had changed a great deal over the previous decades. This was partly because many new items were becoming available: tomatoes, potatoes, tea, coffee, chocolate among many others, all imported by “merchant venturers” from previously inaccessible parts of the world. But we must beware of imagining that most of these were the versions we know. Potatoes were expensive and eaten, like many vegetables, with caution and as a delicacy. A dish of peas was welcome in early summer. The privileged might raise oranges and grapes in their own London gardens. Tea was made in advance and kept in small barrels until needed. Chocolate was a spiced hot drink containing pepper and chili. For those who could afford them, vast roast joints for dinner were still firmly on the menu, but were only part of what was wanted and enjoyed. Sugar was now more widely available and less expensive, and appears much more often in recipes.

With the rise and affordability of printed books, it was now easier to share recipes. Authors such as Gervase Markham and Kenelm Digby wrote and published printed books such as “The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby, Knight, Opened”. These publications were aimed at the educated middle classes, and included advice on gardening, preserving, home medication, preserving and cooking. The prosperous middle class country housewife was expected to oversee her servants and to be able to undertake some of the skilled aspects of house keeping such as preserving and nursing any unwell members of the household. Higher up the social scale a lady was only expected to oversee. For the poor, in the seventeenth century as before and since, it was a case of getting hold of, and possibly cooking, enough food for the next meal.

So what did Restoration Londoners eat and how? The diaries of Samuel Pepys, kept in secret in the 1660s, are an excellent source. Pepys was interested in everything, and was certainly not expecting anyone else to read his diaries, and so talked about everything from work to clothes to quarrels with his wife to food and drink. He was relatively young, on his way up in the world, lived in London quite close to the Tower – and cared very much what he ate, although he did not expect to have to shop for or cook any of it.

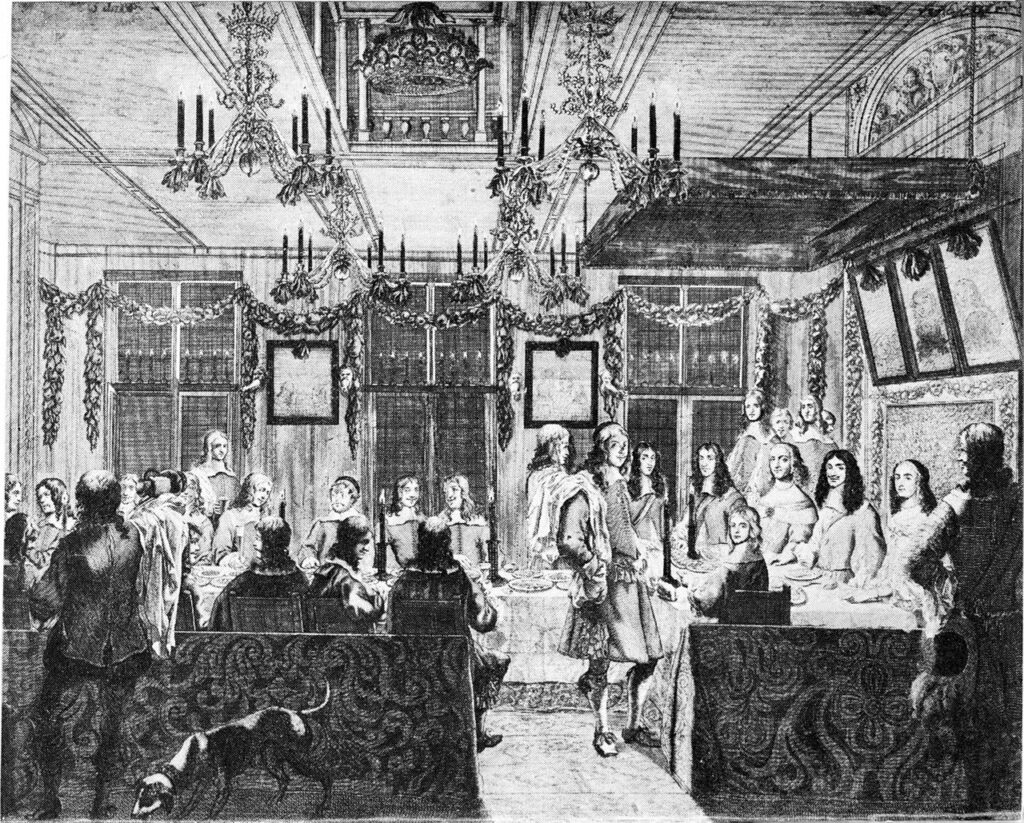

From Pepys and from other sources we can work out that breakfast was still a light meal (often bread, cold meat and ale) eaten early and often in haste. Dinner was still the main meal of the day, now generally eaten in the early afternoon and, for those with the time and money, including at least one hot meat or fish dish. Many London pubs offered cooked food, and Pepys often records eating out, often with friends or colleagues. Pepys, sometimes with his wife, often ate out with friends to socialise, sometimes going by coach to a specific place for a delicacy that was in season – for example an inn in Hackney was famous for cherry and cream in season. Supper, usually eaten in the early evening, was generally a lighter affair, but again was an opportunity for socialising. Pepys records trips to riverside pubs to eat oysters or shrimps, a day out in Epsom by coach, taking with them a picnic of cold fowl, salad and wine and apple fritters on Shrove Tuesday among many other meals out.

Much of the food we read about, both in Pepys and in recipe books, sounds attractive to modern tastes, although some flavour combinations are unexpected. And the habit, when eating meat, of eating the whole animal, gives rise to some recipes, for example sheep’s udder and neat’s tongue cooked together, which might not appeal to everyone. Elaborate salads were popular in summer – of course, in these days before refrigeration, most food was eaten in season. In the Low Countries in particular, still life paintings of fruit and vegetables and game birds were the fashion, all laid out in well appointed kitchens – this demonstrating the affluence and good taste of the home owner. The last seventeenth century equivalent of the interior design magazine.

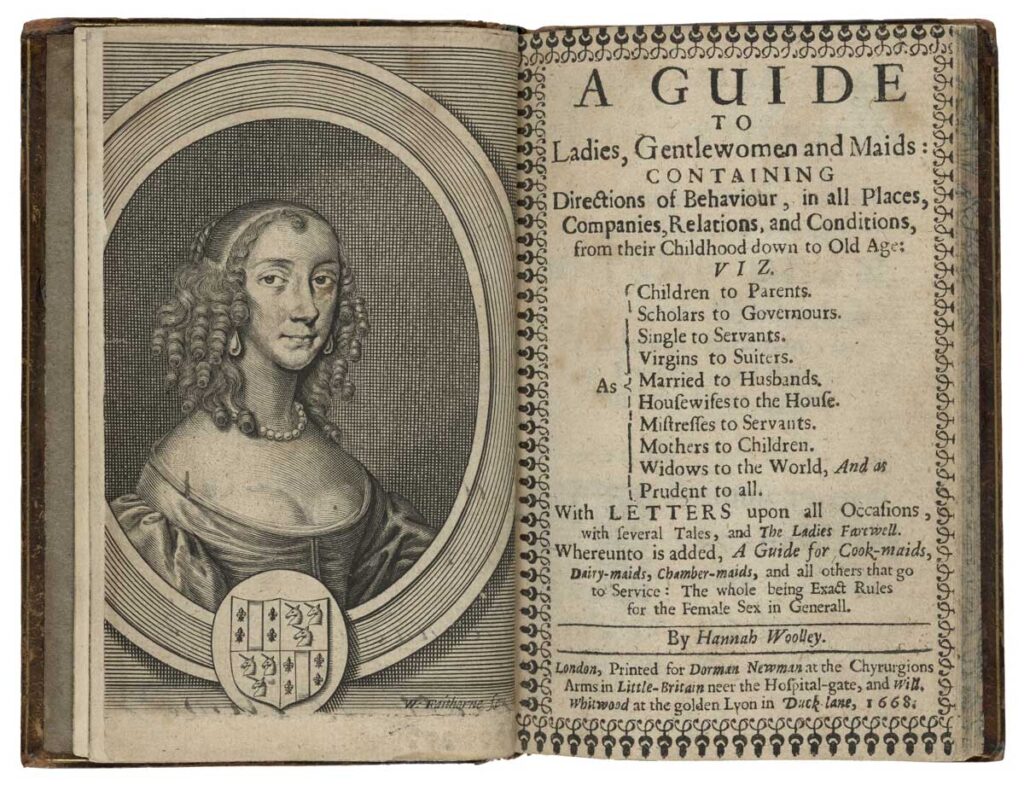

Another source about the food of the time is provided by a female author – Hannah Woolley’s books, which were immensely popular – and reprinted multiple times. Sadly, few of the profits went to the author, as her publisher had updated her work and kept the income for himself. Woolley’s first title was “A Guide to Ladies, Gentlewomen and Maids”, with chapters for women at each stage of life, with sections devoted to many aspects of social life, including “Of the Government of the Eye” – essentially how to avoid flirting – to a large section of recipes for food and medicines. These are mostly fairly elaborate recipes, the sphere of the lady of the house.

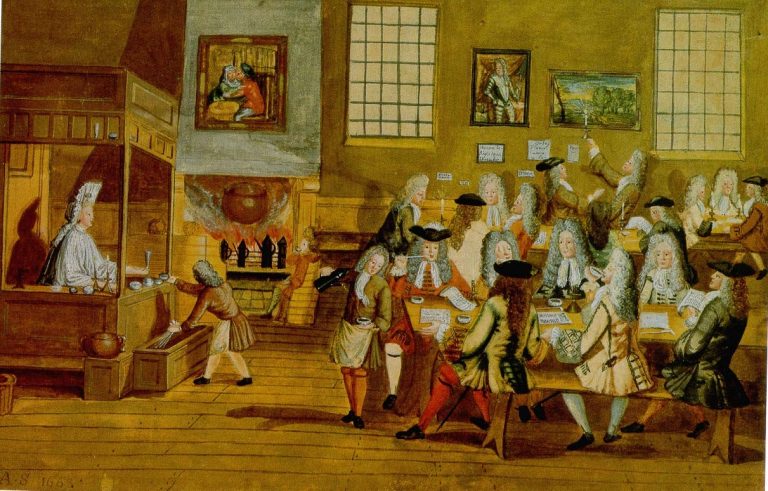

It is hard, however, to imagine Aphra Behn spending her time focusing on creating the perfect pie – something Samuel Pepys records his wife devoting a whole day to when they acquired a new oven. We do not have the details of Behn’s various homes, or even know if she had access to an oven. But given how busy her life was, it seems likely that she frequently ate out (at this time women often ate in an inn) or had food sent round – the Restoration equivalent of the takeaway. The new coffee houses, some of them owned by women, were, however, largely a male preserve.

In and around the theatres, there was fast food to be had. Theatre accounts tell us who had the concession for orange selling. There are also records of stalls in the streets outside offering nuts, ale, rolls and pies. It is tempting to imagine contenting herself with some of these things in passing, and to have returned home after a rehearsal and perhaps a performance of one of her plays to a late night snack.

Clio’s Company (registered charity no. 1101853) is grateful for generous financial support for this project from The Portal Trust