Clothes and appearances

Clothes have always mattered. In Aphra Behn’s lifetime they mattered not only in ways we know about – warmth, cover, fashion, status – but to demonstrate how important or otherwise the wearer was.

And in the early 1640s, when Aphra Johnson, later Behn was a small child, for some people their clothes turned to uniforms as the civil wars began.

Clothes were valuable, expected to last many years, and often left in a will. They were, of course, entirely made by hand using natural fabrics; at this time these consisted of wool, linen and, for the rich, silk. Cotton, although known about and used for furnishing fabrics, was not yet usual for clothes.

It is easy to get the impression that everyone in the 1640s was either the epitome of glamour, or a black-clad puritan. The paintings of Anthony van Dyck record the Court circle of the years leading up to the civil wars, dressed in their best clothes, including shimmering silk and lace for both sexes. During the civil war and commonwealth years, there was little demand for the court clothes of previous years, or for the glamorous portraits that recorded them.

People of lower status wore clothes of the same shapes, but without the silk. As the daughter of a barber surgeon and a wet nurse, Aphra Johnson was one of the middling sort. We do not know for sure whether she spent most of her time with her mother Elizabeth in high status households such as Penshurst, or if she returned at intervals and lived at the pub her father ran alongside his barber’s shop.

Whatever the truth of this, Aphra received a good education, enabling her to move in all levels of society. If it is true she accompanied her mother, Elizabeth, when she worked as a wet nurse in gentry houses, it is likely that she went as a swaddled baby. This meant the baby was wrapped tightly in strips of linen. It was believed that this meant the child felt safe, was kept warm and could not be damaged.

As the baby reached toddler stage he or she was dressed in a long robe, often with an apron and leading bands over the top, and a padded head band to guard against damage from falling over. This outfit was the same for both girls and boys, who were dressed similarly until the age of five or six. At around six, little boys were “breeched” – and with their new clothes went a different status, as they started to be educated as men, whether at school, as apprentices and, for some of the grandest, at home with a tutor.

But most young girls remained with their mothers or nurses. If the theory that Aphra Johnson spent much of her childhood in the nurseries of gentry houses where her mother worked is the correct one, she would have needed the right clothes, just as her mother did. These might have been out-grown clothes of the daughters of the family, adapted to fit Aphra. Young girls past the toddler stage were dressed in miniature versions of women’s clothes. An outfit would consist of a linen smock as an under layer, with a stiffened bodice, laced up the back or front, and a petticoat, usually attached to the bodice.

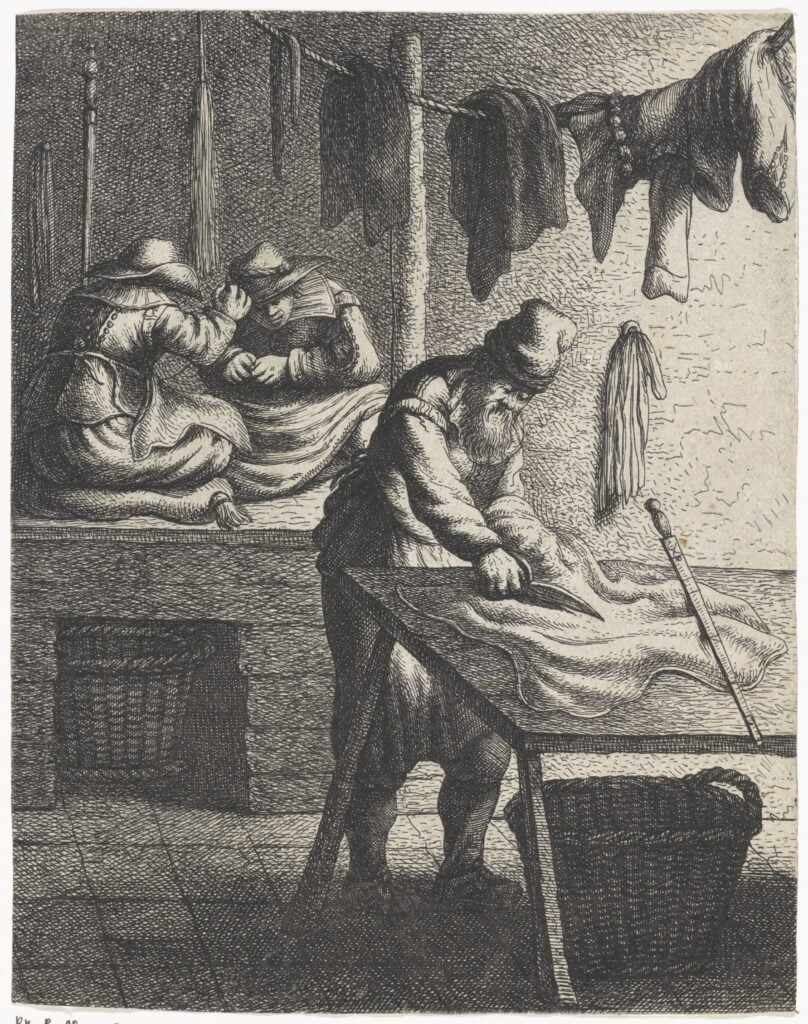

Linen smocks for women and shirts for men would usually be made at home. But outer clothes were more likely to be ordered from a professional tailor, who would attend with patterns and sample fabrics. Once the King was restored in 1660 the demand for court clothes returned. However, the mood of fashion changed, with wigs, long-line jackets and high heeled shoes coming into fashion for men. Women’s clothes now featured pointed bodices ending below the natural waistline, flowing skirts and ordered curls for women.

There is some evidence that Aphra Johnson acted as a spy in her teenage years before her journey to Surinam. If this is correct, she would have needed to look, as well as to behave, like a lady who had reason to travel. She would also need the manners to move in the society in which she found herself. We know she learned to write in an immaculate hand, to speak and write French and a limited amount of Latin as well as to dance and sing.

In the early 1660s, Aphra began a spying career in earnest. The six or eight week voyage to Surinam and several months’ travels overland must have necessitated trunks full of warm and water resistant clothes and shoes as well as cosmetics and medicines. Travel clothes would also include a lined, heavy woollen cloak and a vizard mask to cover the whole face and protect the complexion. This would have been repeated when she went on her second spying mission, this time with a shorter journey, to Antwerp. We have the report letters she wrote; the only mention of what she wore is a series of complaints she has had to pawn her rings to pay for hotel and other expenses – she had been provided with an advance before she left London, but this was an expensive city.

This second spying mission was a disaster – in the end, Aphra had to borrow £150 (the equivalent of several thousand pounds today) to return to London. Only in her twenties and still naïve, she made the mistake of applying too much pressure to the spymasters, who clearly were in the habit of paying by results, which were not forthcoming in this case. Aphra had pawned her jewellery, and arrived back in London destitute. Her second petition to the King tells us she was claiming she had been imprisoned for debt; it seems likely that her foster brother had paid off enough money for her to be released.

Left penniless in Restoration London, Aphra, now known as Behn, (see link to story) needed urgently to find a source of income. Somehow, she found her way into the theatre, first training the next generation as actors, then as a writer, probably working for Sir William and Lady Davenant (link to biography)

Moving in theatre circles meant being seen in the best, most fashionable clothes at all times. As Aphra had arrived back in London deeply in debt, this would have been a problem. She may have stayed in Aldersgate Street with the Davenants in the first instance, and would have been paid both for the workshops she ran with the drama students. But this would not have gone far.

There was a lively trade in second hand clothes in London at this time – from fairly classy shops in suburbs such as Seven Dials to rag and bone stalls on street corners. This passing of garments from hand to hand goes some way to explain why so few survive from this time. It was still usual, too, to leave clothes in wills, from carefully considered bequests of “best” garments to close friends and family to less precious items to servants.

There is no way of knowing for sure how Aphra kept up appearances in her early years in London. But when, with the staging in 1670 of her first main house production, “The Forc’d Marriage”, she became a person of note, the need to dress for celebrity would have become urgent. No will has ever been discovered for Aphra Behn, and it seems likely she had not acquired property, or much in the way of possessions, during her life. Given she was certainly well known in London theatre circles, it may well be that throughout her career much of any money she did make was spent on clothes and on books.

There was the need, too, to be at least as glamorous as the actors she worked with. It was strictly forbidden to cast members to remove costume items from the theatre, and in addition actors were expected to provide some parts of their costumes themselves, although some items were provided by aristocratic well wishers. And given the high value of clothes, the companies guarded the costumes with care, fining company members if harm came to any of them.

At this time theatre costumes were full of fantasy. Historical period and geography were acknowledged, but no one was expecting drab reality to spoil a good story. At this time portraiture was usually approached in the same way. Fashionable artists such as Peter Lely constructed sets in their studios, and subjects were painted against glamorous backgrounds and draped in glowing silk. It was only the cheaper, head-and-shoulders pictures, such as that of Aphra Behn, that offer the viewer only a glimpse of skin, pearls and silk.

By the time of Aphra Behn’s death in 1689, fashion for all, on stage and off, was becoming more vertical and narrow in its lines. For men this meant carefully dressed wigs, coats with ordered pleats and high heels. For women the fashion was becoming tight curls, lace caps, fitted corsets and gowns. It is hard to imagine Aphra and her generation taking to them.

Clio’s Company (registered charity no. 1101853) is grateful for generous financial support for this project from The Portal Trust