Spy Codes of the 17th Century

Coding Before the internet age

Secret codes for writing important messages have been used for thousands of years. The Roman Emperor Augustus devised his own code in 45 BC. Called ‘Caesar’s Code’ it was a fairly straightforward system whereby one letter of the alphabet was substituted for the another a certain number of places further along in the alphabet – thus A became D, B became E, C became F, and so on right round to Z becoming C . This worked surprisingly well for some years, because nobody was expecting it, but over the succeeding centuries early codebreakers could unpick the messages in minutes.

By the seventeenth Century, code writing (cryptography) was well advanced. Users had realised that simply substituting one letter or symbol for another in the text to be coded was relatively easy to decode. For example looking for repeated patterns which could show double letters in the original text, or finding the most frequently used symbols , which would indicate common letters such as vowels or ‘s’, was time consuming, but eventually would make the code breakable. More complex codes had to be devised.

King Charles I and his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria wrote to each other in code throughout the Civil War. One of her surviving letters (in code) expresses some of the problems of using a cipher. A cipher is another name for a code, usually one which needs a special set of instructions or ‘key’ to decode it.

‘Be careful how you write in cipher, for I have been driven well – nigh mad in deciphering your letter. You have added some blanks which I had not, and you have not written it truly. Take good care I beg you, and put in nothing which is not in my cipher… let not our cipher be stolen’ Henrietta Maria to Charles I March 1642

There are many more examples of ciphers and codes used by Charles I and other to various recipients, some of which can be found on various websites, such as

https://archives.blog.parliament.uk/2020/04/27/cracking-the-code-love-war-and-letters/

There were many different ciphers in use during the English Civil War: some surviving letters have still not been deciphered because the key has been lost. For an example of this see

Where after many years the museum staff have finally cracked the cipher used by Lord Fielding (a senior diplomat of the time) but still can’t read the document because it is in mediaeval French.

See the section of the website on the civil War and spying for more details on the reasons for needing secret codes, and the people who used them.

The Vigenere Cipher

One of the most frequently used secret codes of the time was called the Vigenere Cipher, named after a French diplomat. Despite its principles being known to many, it was, and still is, hard to decipher due to the use of a key word or phrase, known only to the correspondents.

Here is how it works.

Alphabetic version

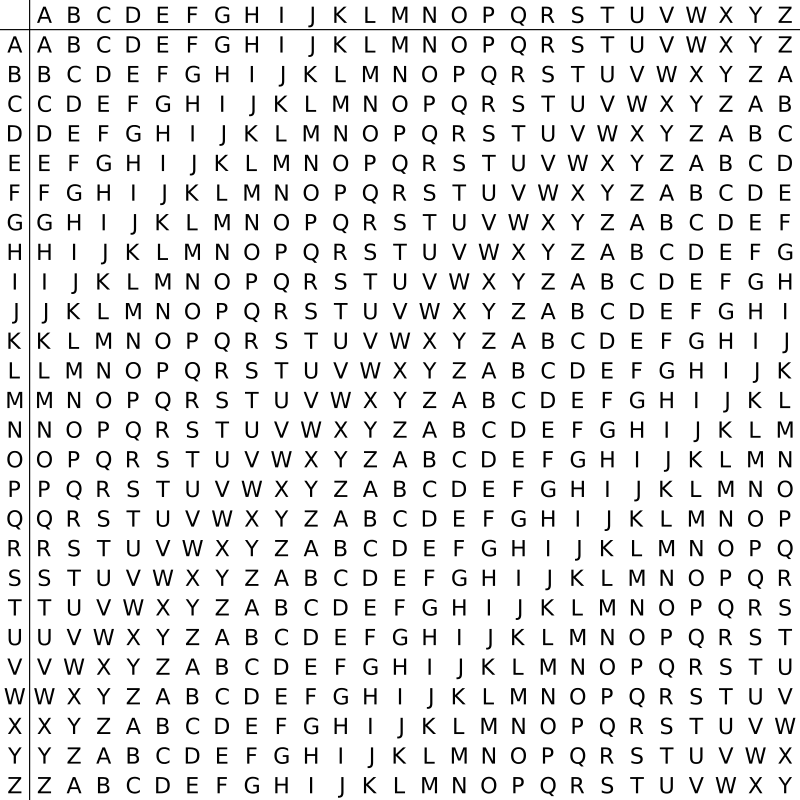

Create a grid of letters of the alphabet, the size of which is known to the correspondents. The grid on the left is probably the most useful one to start with.

This gives twenty six permutations of the alphabet.

There are ROWS, going across, and COLUMNS going down the grid.

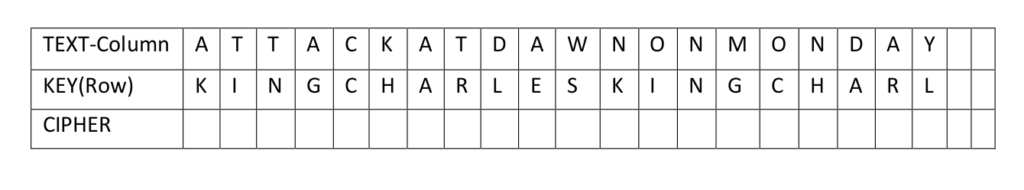

The conspirators need to have an agreed codeword or phrase, preferably with few repeated letters, as an example KINGCHARLES.

The message to be coded is written out: for example

ATTACK AT DAWN ON MONDAY

And the keyword is repeated underneath it until it is the same length as the original text

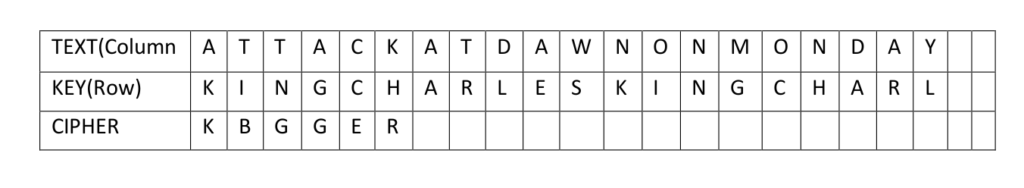

Using the alphabet grid, find the ROW that has the letter of the KEYWORD (K) and the COLUMN of the TEXT (A) The cell where the row and column meet gives K as the first letter of the coded message.

Repeat for the second letter – the KEYWORD is I and the TEXT T which gives the letter B for the code.

Continue for the whole message – a pair of rulers or a large set square are very useful tools to keep the coding accurate.

To decode an encrypted text, reverse the process. Find the row which corresponds to the keyword letter, find the cipher letter, and track that back to the left hand column, which will give the original message.

Write your own spying letter; you may choose only to encode the most important words. Try not to make your key word or phrase too obvious: if the Royalist plotters had used ‘King Charles’ as a key phrase, the Parliamentary Secret Service would probably have decoded it quite quickly. Do not forget your key word, but make sure that only the person you are writing to knows it.

Clio’s Company (registered charity no. 1101853) is grateful for generous financial support for this project from The Portal Trust